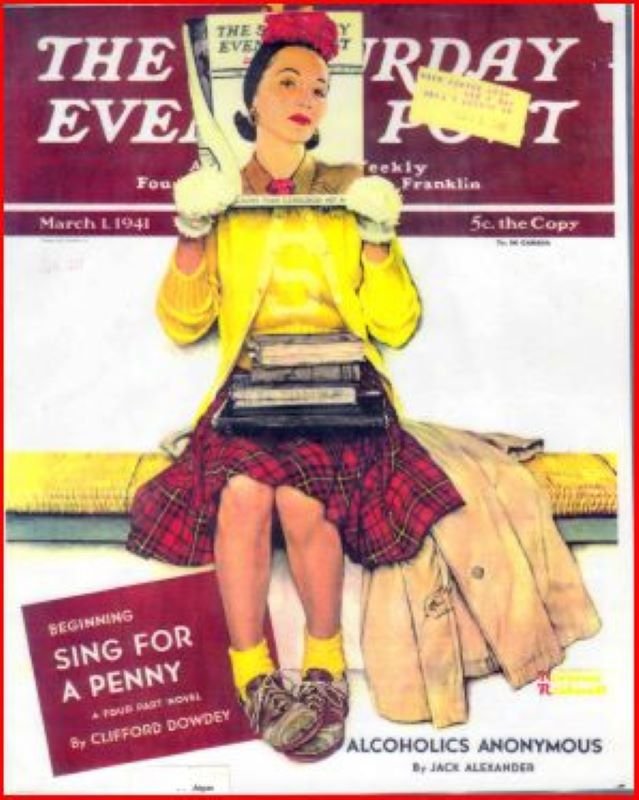

The Saturday Evening Post

The History of How the Article Came To Be Jack Alexander of Saturday Evening Post Fame Thought A.A.s Were Pulling His Leg

AA Grapevine, May, 1945

“Ordinarily, diabetes isn’t rated as one of the hazards of reporting, but the Alcoholics Anonymous article in the Saturday Evening Post came close to costing me my liver, and maybe A.A. neophytes ought to be told this when they are handed copies of the article to read. It might impress them. In the course of my fact gathering, I drank enough Coca-Cola, Pepsi-Cola, ginger ale, Moxie and Sweetie to float the Saratoga. Then there was the thickly frosted cake so beloved of A.A. gatherings, and the heavily sweetened coffee, and the candy. Nobody can tell me that alcoholism isn’t due solely to an abnormal craving for sugar, not even a learned psychiatrist. Otherwise the A.A. assignment was a pleasure.

It began when the Post asked me to look into A.A. as a possible article subject. All I knew of alcoholism at the time was that, like most other non-alcoholics, I had had my hand bitten (and my nose punched) on numerous occasions by alcoholic pals to whom I had extended a hand–unwisely, it always seemed afterward. Anyway, I had an understandable skepticism about the whole business.

My first contact with actual A.A.s came when a group of four of them called at my apartment one afternoon. This session was pleasant, but it didn’t help my skepticism any. Each one introduced himself as an alcoholic who had gone “dry,” as the official expression has it. They were good-looking and well-dressed and, as we sat around drinking Coca-Cola (which was all they would take), they spun yarns about their horrendous drinking misadventures. The stories sounded spurious, and after the visitors had left, I had a strong suspicion that my leg was being pulled. They had behaved like a bunch of actors sent out by some Broadway casting agency.

Next morning I took the subway to the headquarters of Alcoholics Anonymous in downtown Manhattan, where I met Bill W. This Bill W. is a very disarming guy and an expert at indoctrinating the stranger into the psychology, psychiatry, physiology, pharmacology and folklore of alcoholism. He spent the good part of a couple of days telling me what it was all about. It was an interesting experience, but at the end of it my fingers were still crossed. He knew it, of course, without my saying it, and in the days that followed he took me to the homes of some of the A.A.s, where I got a chance to talk to the wives, too. My skepticism suffered a few minor scratches, but not enough to hurt. Then Bill shepherded me to a few A.A. meetings at a clubhouse somewhere in the West Twenties. Here were all manner of alcoholics, many of them, the nibblers at the fringe of the movement, still fragrant of liquor and needing a shave. Now I knew I was among a few genuine alcoholics anyway. The bearded, fume-breathing lads were A.A. skeptics, too, and now I had some company.

The week spent with Bill W. was a success from one standpoint. I knew I had the makings of a readable report but, unfortunately, I didn’t quite believe in it and told Bill so. He asked why I didn’t look in on the A.A.s in other cities and see what went on there. I agreed to do this, and we mapped out an itinerary. I went to Philadelphia first, and some of the local A.A.s took me to the psychopathic ward of Philadelphia General Hospital and showed me how they work on the alcoholic inmates. In that gloomy place, it was an impressive thing to see men who had bounced in and out of the ward themselves patiently jawing a man who was still haggard and shaking from a binge that wound up in the gutter.

Akron was the next stop. Bill met me there and promptly introduced me to Doc S., who is another hard man to disbelieve. There were more hospital visits, an A.A. meeting, and interviews with people who a year or two before were undergoing varying forms of the blind staggers. Now they seemed calm, well-spoken, steady-handed and prosperous, at least mildly prosperous.

Doc S. drove us both from Akron to Cleveland one night and the same pattern was repeated. The universality of alcoholism was more apparent here. In Akron it had been mostly factory workers. In Cleveland there were lawyers, accountants and other professional men, in addition to laborers. And again the same stories. The pattern was repeated also in Chicago, the only variation there being the presence at the meetings of a number of newspapermen. I had spent most of my working life on newspapers and I could really talk to these men. The real clincher, though, came in St. Louis, which is my hometown. Here I met a number of my own friends who were A.A.s, and the last remnants of skepticism vanished. Once rollicking rumpots, they were now sober. It didn’t seem possible, but there it was.

When the article was published, the reader-mail was astonishing. Most of it came from desperate drinkers or their wives, or from mothers, fathers or interested friends. The letters were forwarded to the A.A. office in New York and from there were sent on to A.A. groups nearest the writers of the letters. I don’t know exactly how many letters came in, all told, but the last time I checked, a year or so ago, it was around 6,000. They still trickle in from time to time, from people who have carried the article in their pockets all this time, or kept it in the bureau drawer under the handkerchief case intending to do something about it.

I guess the letters will keep coming in for years, and I hope they do, because now I know that every one of them springs from a mind, either of an alcoholic or of someone close to him, which is undergoing a type of hell that Dante would have gagged at. And I know, too, that this victim is on the way to recovery, if he really wants to recover. There is something very heartening about this, particularly in a world which has been struggling toward peace for centuries without ever achieving it for very long periods of time.”

Jack Alexander

Philadelphia, Pennsylvania